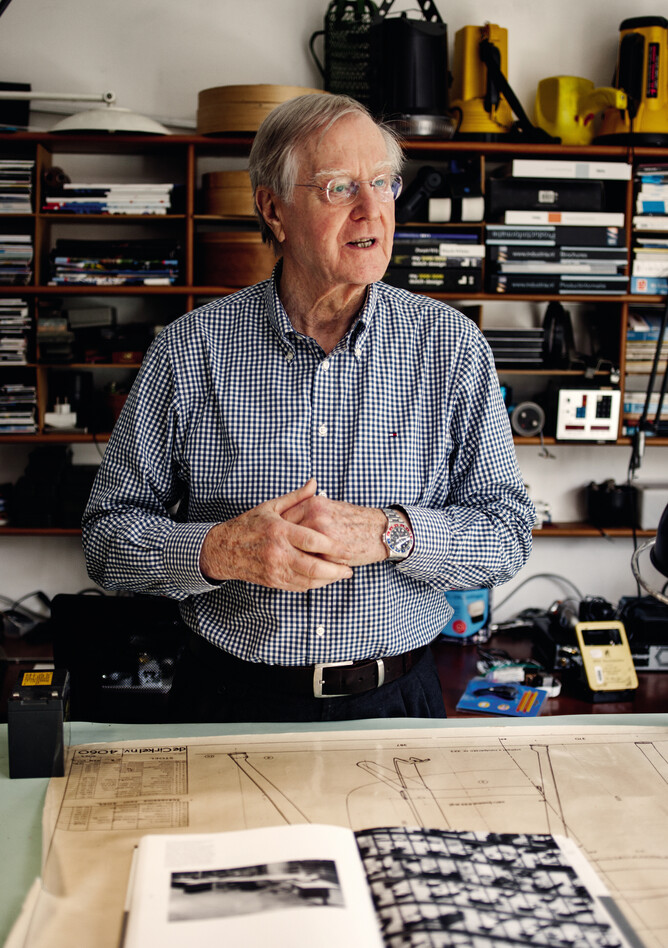

Friso Kramer

Friso Kramer was a quirky modernist. He believed in 'form follows function' and 'less is more'. Not as dogma but as outcome of human involvement. That was the essence of everything. The simplicity of his designs , meant that they were not eye-catching; yet everyone recognises at least one of his designs. This makes Friso Kramer the most famous, unknown designer. One of The Netherlands' largest industrial designers, he was a rare foreigner who was crowned with the English title; Royal Designer for Industry.

Simplify Design

Generations grew up with his products. His green mailbox met the mailman in the front yard. His street light lit the night walker and not the sky 'because the moon and the stars already do'. Friso Kramer preferred to design for society, with attention to the quality of appearance, construction, choices of materials and ergonomics. All his designs have a self-evident simplicity. He always claimed; ‘If a product wants to respond to a broad social purpose, it must be as anonymous as possible.'

Designer

His father built department stores as 'palaces for the worker'. His teachers had been linked to the progressive Bauhaus in Dessau. When Friso Kramer started working as an industrial designer after the war, a straight forward and human attitude towards his designs had become the essence of his work, which he believed was the only right starting point. He lived in Amsterdam and near him was De Cirkel, Ahrend's production company. "a mutual contact of me and the director of De Cirkel has made the first contacts." He started as a constructive draughtsman but soon became a designer for the factory. In 1963, he founded the influential design agency Total Design with others, and eight years later he returned to Ahrend, now as art director and executive.

Solutions

"If someone comes up with a problem, it inspires me to come to a solution," he once said of himself. When he developed a chair or table for Ahrend, it seemed as if human civilisation had yet to start and a chair or table had to be designed for the first time in history. The result was almost always archetypal designs: the Revolt chair (1953), the Revolt drawing board (1957), the modular Facet tables (1964) and the Office System Mehes (1972), the significant acronym of Mobility, Efficiency, Humanisation, Environment and Standardisation. Still to this day, these are the five pillars that Ahrend's design policy stands for.

Boundless perfectionism

If Friso Kramer was talking about industrial design, he pretended his role as a designer was easy, simply serving, that's all. In reality, behind his words and the simplicity of his designs, was an immensely complex design process, a boundless perfectionism as well, and years of product development. "You have to walk through the factory for days, look, think how it can be more efficient." he once said. "You have to look and find all the excess elements, track down, cut off, throw it away and see what's left and get back to work with what remains." It sounded like he was an engineer, analyst, surgeon and sculptor at the same time.

'Friso Kramer was one of the few Dutch designers who came up with really new solutions,' a museum curator once said about him. When he developed the Revolt using unconventional steel, the chair unleashed a revolution. Light, slender and indestructible, he modernised the post-war Netherlands. Not only was the chair a breakthrough in the field of design, it was also one of the first real mass produced items of furniture.